Last summer, Professor Paulina Alberto, associate professor of History, Spanish and Portuguese, and I obtained a Spring/Summer Research Partnership Grant from Rackham, to work toward her second book project, “Racial Stories: Lives and Afterlives of Argentina’s ‘Negro Raúl’ (1880-present)”. The project for the summer was to learn emerging methods from the digital humanities (e.g. text mining, network mapping, and topic visualization) and to apply them to her existing documentary corpus.

Paulina’s corpus includes cartoons, photographs, newspaper and magazine articles, films, plays, novels, short stories, poems, memoirs, political propaganda, histories, and song lyrics from the early 1900s to the present, all of which narrate episodes in the life of Raúl Grigera (a.k.a. “El Negro Raul”), an Afro-Argentine man who became famous during the first three decades of the twentieth-century in Argentina.

The project’s main objective was to learn whether and how these techniques of “distance reading” can provide new ways of getting at the questions about history, race, and narrative that are central to our scholarship. Specifically, Paulina hoped to learn whether distance reading could help further reveal and document visible patterns (repeated words, tropes, images, as well as connections among writers and publications) in the hundreds of texts about Raúl Grigera—patterns that reflect the ways in which dominant ideologies of race shaped storytelling about this singular character.

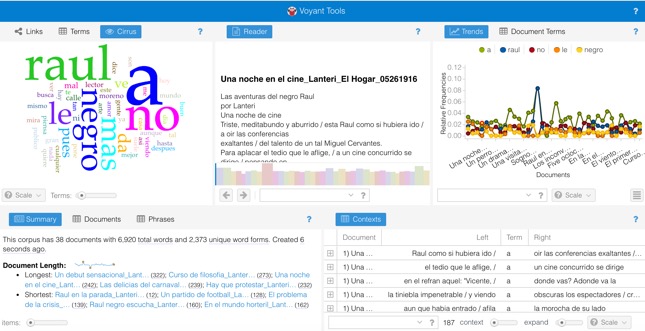

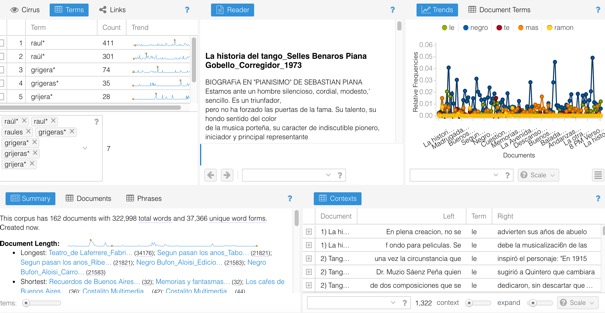

I spent the month of May getting familiar with the corpus and attending hands-on workshops that presented different digital tools for text-mining analysis. I learned a bit of Python, but my initial experimentation was with Voyant, as it was easier to start playing around with.

Before my immersion into distance-reading technologies last summer, we had only the questions and hypothesis drawn from Paulina’s previous close readings of the texts and my own observations of themes and patterns in the corpus (with which I became quite familiar in the process of reading, transcribing, and preparing the texts for digital study).

First experiments with Voyant.

My initial experiments with Voyant toward the end of the summer began to reveal some new areas for further research; specifically, I have been able to track, the repetition of several key words and phrases over time and across genres with much more statistical precision. I’m including below some some of the outcomes of these analysis:

Some initial arguments and hypothesis:

-

“Afterlives”: Script – Plagiarism and circular references – demise of the once substantial Afro Argentinean population– Raul as exception – no lineage, no history, no larger community.

-

Raul also served as an object lesson for the emerging Argentine middle class. Lanteri’s cartoons – Middle class morality.

Voyant outcomes:

- Analysis of “Post 1930” section of the corpus (texts written after 1930s). Word recurrence: “Raul/ Raúl”: 702 times – “Grigera/Grijera/Grigeras/Grijeras”: 151 times

- Analysis of “El Hogar – Aventuras del Negro Raul” section of the corpus (Composed by cartoons that appeared during the year of 1916 in the magazine “El Hogar”). Word recurrence: ”Moraleja” (Moral): 37 times – “Piensa” (Thinks): 11 times – ”Tilingo” (Silly and Superficial): 6 times – “Mundo” (World): 10 times.

Limitations.

Nevertheless, although new patterns emerged, I’m aware that I ran my experimentation using supervised models and techniques, as Ted Underwood explains in Seven ways humanists are using computers to understand text. In this sense, I do agree with Shlomo Argamon et al. when they write that:

“Text mining opens new avenues of textual and literary research by looking for patterns in large collections of documents, but should be employed with close attention to its methodological and critical limitations”.

For instance, some of the limitations I found were in terms of language and word recognition. My database is in Spanish and the stopwords list that Voyant uses is quite imprecise. I had to use a different stopwords list and to reload it every time I was running a new analysis, which made the process slower. Moreover, the corpus contains from publications that appeared in magazines and newspapers, to academic articles and memoirs. The language was thus different for each of the genres and that also made difficult to identify common words that appeared across the texts. Lastly, the length of the texts moved from one page in the case of cartoons to hundred of ones in the case of plays or even historical analysis. That also affected the results, as the different texts weighted differently and longer texts’ vocabulary was predominant in the results showed.

What now?

In spite of the limitations listed above, I consider distant reading techniques as valuable methods for discovering new connections between texts, connections that would be invisible to a close reading approach, and to reinforce our existing hypothesis and arguments. Said that, I feel that is now crucial to start experimenting with some more advanced techniques for text mining, tools that will allow me to go further in these analysis and to open up new questions and connections that we may not be thinking now.

... Back to top ...